When it comes to fame, Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) strikes me as being right up there with Rembrandt in the minds of the general public. No other modernist artist comes close except, perhaps (in the USA, anyway), that other master of self-advertisement, Andy Warhol.

From what I've read, the young Picasso impressed other artists with his existing and potential talent even before he helped invent Cubism. I make no secret of my dislike for nearly all of Picasso's work, but I'm willing to explore the work he did when young as grist for speculation regarding his ability and whether or not he could have carved out a career as a representational painter.

For background and information about his early paintings, I consulted the first volume of John Richardson's uncompleted multi-volume biography of the artist.

Picasso's father was an artist and art teacher whose work Richardson considered inferior. Still, one can assume that Picasso could not have failed to absorb many nuts and bolts of the craft of oil painting by the time he entered his teens and began attempting serious work. While in his teens he received some formal training but did not go through the complete rigorous academic regimen still in place in the 1890s. He was done with schooling before he turned 19.

Now let's look at a sample of his paintings that basically can be considered representational in style; I've ordered them by year. Keep in mind that Picasso was born in late October of 1881 and do some subtracting from the painting dates to get an idea as to his age at the time.

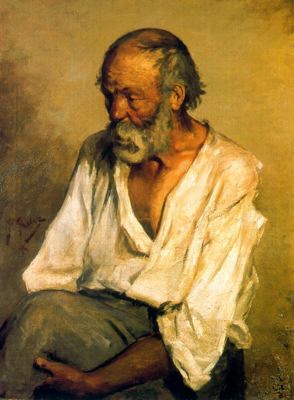

The Old Fisherman (Salmerón) - 1895

First Communion - 1896

Click on image for a larger, clearer view.

Altar Boy - 1896

Click on image for a larger, slightly clearer view. I saw this at the museum at Montserrat, a few miles west of Barcelona. It struck me as being smoothly painted, an attribute this reproduction fails to show.

Ciencia y Caridad (Science and Charity) - 1897

This was painted as a salon entry.

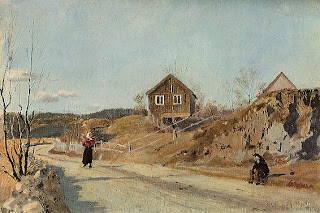

Moulin de la Galette - 1900

Painted the year Picasso first visited Paris.

Mujer en azul - 1901

Richardson suggests this painting reflects the influence of Goya.

Self-portrait (Yo Picasso) - 1901

The drawing is representational, the technique is "painterly" and the colors seem early Fauvist, even though Picasso wasn't identified with that movement. Richardson also notes (Page 417) that Picasso was never strongly interested in color -- a Spanish thing, it seems.

Woman in Mantilla (La Salchichona) - 1917

Here Picasso experiments: a smoothly-painted face contrasted with pointillist technique.

Portrait of Olga - 1917

Click on image for a larger, clearer view.

Olga Picasso - 1923

Here he was as representational as he ever got in the years following Cubism. Even so, this portrait and the one above simplify to the point where a bit too much crispness (from a reality standpoint) creeps in. This tack was taken by many artists in the 1920s and 30s wanting to introduce a whiff of modernism to their paintings. Click on image for a larger, clearer view.

Did Picasso have the Right Stuff to succeed in representational art?

I think he did, though I have trouble evaluating the ability displayed in the earliest, most representational, works. Richardson does not consider Picasso's mid-teens efforts outstanding, though he fails to offer a yardstick for this opinion.

My problem here is that I don't hang out around art schools of any kind, let alone those inhabited by 15-year-olds; I have no idea how good a painter that age might be.

The yardstick I do have is myself. At ages 15-20 I did not paint nearly as well as did Picasso, nor do I recall any fellow student who did. On the other hand, our training was close to non-existent. As best I remember, high school art classes basically were sessions where we fiddled around drawing or maybe using water-based media and the teacher's role was that of a gentle critic. College was more of the same, except that we got less than a bare minimum of instruction and also began working in oils.

It's too bad we can't invoke a parallel universe where Picasso studies at the Académie Julian under, say, William-Adolphe Bouguereau or perhaps elsewhere under Jean-Léon Gerôme or Carolus-Durand. If so, the kid coulda had a future.